Caps with a simple rectangle for a headpiece appear early and late in the 18th C. This cap is probably an early one, but with so little to compare it to, it’s best guesses all around. Its home is the McCord Museum in Montreal, Canada, #M980.4.26. It does not have an online record. The museum dates this cap as “late 17th? or early 18th” Century. If that’s true, it is the oldest cap I have found.

The Original

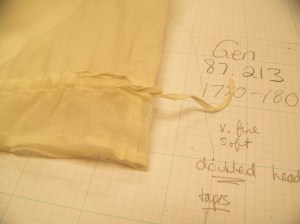

This one is very simple: a half-circle caul of linen attached to a rectangle of lace for a headpiece. A tape gathers the caul at the nape, as is common.

The large size assures me this is an adult cap: 9″ high by 9.5″ from back to front edge. The caul is made of two pieces, felled together down the center back line, with about 10 big stitches per inch. The front edge of the caul is hemmed back with a 3/8″ seam. There aren’t any gathers sewn in. The only gather is the drawstring along the bottom, which isn’t drawn through any casing in the cloth, but caught up within a looped string. Two tapes, anchored at opposite ends, pull across one another through these loops to effect the gather.

The headpiece is a rectangle of lace with a motif of birds and flowers. Is is whipped onto the caul with big uneven stitches. The bottom edge is finished with another piece of lace sewn on that is about 1/2″ wide; the front is edged with a piece that is about 1/4 wide. This makes me think the large lace piece is cut on those edges. One of the points has a small loop – for a tie or button? Please someone who knows lace come behind me here and help with the lace description!

Questions that remain

Other Squared caps that we have access to are few. Burnston covers two of these in Fitting and Proper, pps 35-37. She dates these 1790-1810. (West Chester, PA., items # 1989.1995 and # 1994.3270; I got to see 1994.3270, but didn’t see 1989.1995) Her descriptions in that book are clear and detailed, so I won’t repeat them here. The other place a squared cap is described is in Rural Pennsylvania Clothing. (Caps C and E, pp 68-69.) Gehret notes these caps are late 18th C (some say they are even later.). All that to say there isn’t much to compare this cap to, especially if we want to date it to the early 1700’s.

Being housed in Montreal also adds the complication of possible French influence. The museum record notes the provenance as “Antwerp?” so it might be Belgian. If so, it is technically outside the scope of this study, in which I am trying to keep to items from places that became the United States.

Still, if it is “late 17th, early 18th” century, it is the oldest adult cap I have found.

Portraits

Few portraits show caps with squared headpieces. Or, we might say, in few portraits are we sure we are seeing a really squared headpiece. In many portraits, the cap is high and back too far to be sure; only the ruffle suggests the shape.

Ann Pollard was 100 when she had her portrait made. Her caps looks definitely squared at the edges. Since she is aged, I wonder if this was old fashioned at the time? I’ve only found 2 other portraits with the same shape cap, and they are also early.

Then, in the 19th C, they show up again, and styles take off with additions of deep lace & ruffles, inserts and embroidery.

The Reproduction

I haven’t made a repro of this cap yet.

My Notes

Click here for notes: mccord 980.4.26 notes

Thank Yous and Permissions

Thank you to Alexis Walker, Curatorial Assistant, Costume and Textiles, who corresponded with me and helped me at the McCord. I have written for her permission to use these images and discuss this artifact here.

Photos by the author.

Other Related Scholarship

I am not aware of any other scholarship on this cap.

Final. This is the last cap description.