Another of those rare birds: a cap with provenance. This one, held at Winterthur Museum, #1982.0064, was part of a group of needlework passed down through the Canby-Ferris family. The note with this cap reads, “Great-great grandmother Martha Canby’s cap – died 1826.” She was married in 1774, but no birth date is included. That puts the majority of her life before 1800, and no construction details make me think otherwise, so I accept this as a possible 18th C cap.

The Original

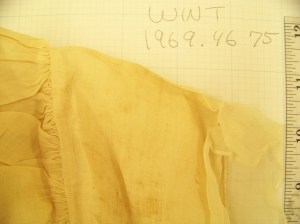

Martha’s cap is a well crafted example of what later became Quaker fossilized fashion in caps. A simple lappet, with no lace or froufrou. Made in three pieces: caul, headpiece, ruffle. The only gather is around the tip of the lappet where a short tape ties it under her chin; the caul is gathered with “kissing strings.” The ruffle skinnies as it goes around, and ends about 1 3/8″ back along the caul, but doesn’t wrap around the back.

Every edge is first finished with a rolled hem. The bottom of the caul has a channel just big enough for the long strings that gather it. I hadn’t figured it out yet, but I think these are attached on either side after going through the channel. So they criss-cross in there, and pull at the opposite side. They come out where the caul and headpiece meet under her ear, on top of the ruffle. These strings aren’t tapes; they are small round strings. (Is that a datable clue?)

The top of the caul is whip gathered across the top 6″, then whipped to the headpiece along the rest of the join.

The ruffle goes from 1 1/2″ at the CF, and gradually skinnies down to 1″ at the turn, and 1/2″ by the time it gets to the end. I’ve pondered that before. But this is the most extreme example so far. The front of the ruffle seems to stay on the straight grain, so the difference happens on the join. You can see my confusion in my notes. I kept marking the grain as straight, but the width changed; what was changing? the ruffle? the headpiece? Answer: ruffle. The two finished edges of ruffle and headpiece are whipped together, and the seam is immeasureably small. Go ahead, zoom in on that seam. I wish my photos were clearer. I’d like to get another look at this cap.

The headpiece has a really narrow point, only 1/4″ across at the skinniest. The point is reinforced to hold that 5″ long tape. I’m not sure I’m looking forward to trying to reproduce that very small detailed work. The back edge of the lappet, from tip to under the ear, has a nice curve; sometimes that line is rougher, or straighter.

0verall, Martha’s cap is 11 1/4′ tip to stern, 8 1/5″ at its widest point laid flat.

Questions that remain

My notes say, “Tape sewn to outside,” yet the picture shows clearly that the tape is on the inside. That’s because I was confused with this one, whether it was being stored inside out or not. That isn’t unheard of; I’d already seen a couple like that. 18th C seams can be so incredibly perfectly minutely made that you really have to look hard to determine inside from out. I think I had decided this one was inside out. You look and see if you can tell — again I wish my pictures were clearer. I only have an average camera, and lighting isn’t always photo-friendly.

Have I ranted enough about the sewing here? This one reminds me of the fineness of Mary Alsop’s cap. I’ve wondered if the edges I’ve seen are really selvages. That is, what I am seeing is not two edges rolled, then whipped, together, but two selvages whipped together. How could I ever tell? But this example, where the inside edge of the ruffle is NOT along the grain, sort of proves that edge, at least, is a hand-rolled edge.

The Reproduction

I haven’t reproduced this one yet. You try it, and share your attempt with us, OK?

My Notes

Click here for notes: notes wint 1982.0064

Thank Yous and Permissions

Linda Eaton, Senior Curator of Textiles, gave me permission to discuss this artifact here. Lea Lane met me at the museum that day and helped me with questions afterward.

Photos by the author.

Other Related Scholarship

This cap appeared in Winthurtur’s exhibit, “Who’s Your Daddy?” The Exhibit Guide, Page 4, includes this cap, and references Martha’s ownership.

Final.