[2nd draft. pics rev ]

In all my travels, I have found only two round-eared caps from the 18th C. They are both at the Smithsonian, both from the Copp Collection. The other one is described here .

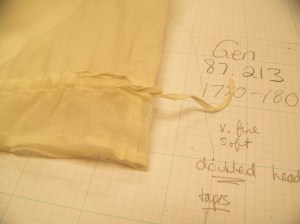

The cap is housed in the textiles collection of the National Museum of American History.* The record for this item is not online.

The Original

The museum dates this cap 1795-1815, so it just barely qualifies as 18th C. Since we can’t ask the curator who assigned these dates so long ago, we don’t know what that person saw to prompt her to date this one later than Smiths 6608. I think that the wider hems and cotton cloth are clues to a later date.

Made of cotton mull, superfine and almost gauzy, plain white, with an edging on the ruffle (it isn’t lace; an extra fine tape, perhaps?). My notes are unclear here. (Argh! even when you think you’ve been thorough…)

It’s made of three pieces, all on the straight grain: semicircular caul, 1 3/4″ straight headpiece, and a ruffle that’s wider at the CF than the bottoms. The headpiece is pieced at the top with a felled hem. That’s pretty common. Gathers on the caul and the ruffle are rolled, whipped, gathered all in one stitch, making a pretty popcorn effect inside that goes across the top 4″ on the headpiece, the top 8″ on the ruffle. The headpiece is hemmed 1/8″ all around, and the hem of the ruffle is 1/4″. A casing runs along the bottom of the caul and headpiece, allowing the strings to come out right under the ears.

Questions that remain / Portrait

What don’t I understand? The two round-eared caps have straight headpieces. I keep recommending Kannik’s cap pattern, but really her cap isn’t like these at all. That cap I wear, that I’ve replicated a dozen times, has a moon-shaped headpiece, and a shaped ruffle that is gathered all the way down. Many French portraits have detailed renderings of caps, but for American caps, Mrs. Brewster is abut the only one I can see any detail. This portrait is 1795-1800, so it fits the time period given the cap. I think her headpiece is straight, too.

And what do you do with those gathering strings once you’ve pulled them? Where do they hang? Where do you hide them? They would be looping down under your earlobes. Tie them under your chin?

The Reproduction

I had a nice soft cotton to work with, and the repro matches the original shape and size. The caul pattern is off; I had to make adjustments as I went, and I noted “redo this” on the pattern, so don’t trust it!

Having the gather string go all along the bottom and tie under the chin, plus the really wide ruffle, gives this cap a halo effect when worn.

My Notes

smiths 6608 B round notes and pattern

Thank Yous

Nancy Davis, Curator of Textiles at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, helped me to identify items in that collection that were useful to this study. That was no small feat, as records were spread across several legacy cataloging systems, and details were minimal. I can only hope I found what there was to find!

Other Related Scholarship

I am not aware of any scholarship for this artifact.

*. . . which is not the same thing as the Smithsonian’s Cooper Hewitt, in NYC. Their textiles section was under construction at the time of this study, so I didn’t get to see their artifacts.