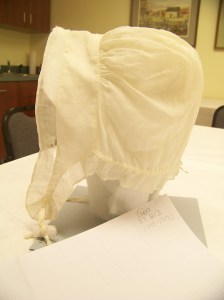

The ruffles of most lappets are barely gathered except for the turn at the point of the lappet. But some also have a tuft of tight gathers at the Center Front (CF), like a corsage of little flowers on top of your head. Smithsonian 6608-D has that extra flair.

The cap is housed in the textiles collection of the Smithonian’s National Museum of American History*, a part of the Copp Collection. The museum date is 1775-1799. The record for this item is not online. I found a great picture of this collection on display at the museum in 1894.

The Original

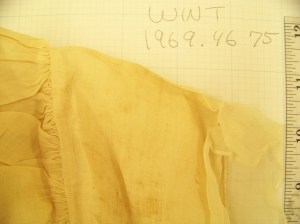

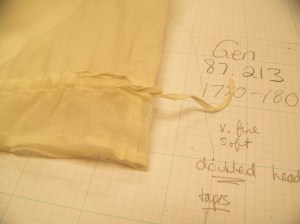

Heavy linen cloth gives this cap a unique feel and weight.

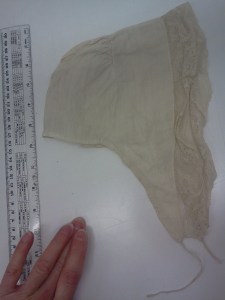

The structure is the same as most 18th C lappets: caul, headpiece, ruffle.

This ruffle goes all the way around the back, so when the gather around the bottom of the caul is pulled to fit, it creates a ruffle at the nape of the neck. The gather string comes out of a buttonhole inside.

The outer edge of the ruffle is hemmed 1/8″; the inner edge alternates between a rolled gather where needed and a minute whip. The headpiece is hemmed 1/8″ all around, and joined to the ruffle with a whip stitch. The caul is sewn the same: hem, rolled gather, whipped to the headpiece. The whole work is as neat and tidy as… an 18th c cap.

I love seeing the human element in an artifact. This cap is nearly perfect, but the hem around the lappet gave the seamstress some trouble. There’s the edge awkwardly folded, a little bunchy on the turn. Part of that has to be the heaviness of the cloth. Getting around the lappet has often left me cursing, too.

The short ties under the chin are 1/8″ tapes, probably linen, sewn on to the hem of the headpiece for strength.

Questions that remain

I wonder if the weight of this cloth means it had a specific use? Heavier for night time? For winter? I’ve only seen this weight of cloth a handful of times. The hood-like cap from the Philadelphia museum is one.

Also, can I call that nape ruffle a bavolet?

Portraits

Abigail’s cap is a lot like this one. It has a ruffle that goes all the way around her neck, and that extra little fancy bit at the top of her head. Her ruffle appears to be several layers, doubled at least, possibly tripled, which really makes me wonder how it is made. She has tied her cap with a pretty bow matching her gown. There might be a white ribbon over the headpiece, too.

This corsage effect I’ve seen mostly in mid-century portraits, 1750-1770. The museum date of the last quarter would be a little late, then?

The Reproduction

No repro yet.

My Notes

Click here for notes: smiths 6608 d notes

Thank Yous and Permissions

Nancy Davis, Curator of Textiles at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, helped me to identify items in that collection that were useful to this study. That was no small feat, as records were spread across several legacy cataloging systems, and details were minimal. I can only hope I found what there was to find!

Photos by the author.

Other Related Scholarship

I am not aware of any other scholarship about this cap.

*. . . which is not the same thing as the Smithsonian’s Cooper Hewitt, in NYC. Their textiles section was under construction at the time of this study, so I didn’t get to see their artifacts.

Final.